Early Biographies

1Andrew Chinn and Fay Chong shared a Chinese heritage. Their families were part of a mass migration that left southeast China in search of economic opportunities along the West Coast of the United States. Chinn was born in Seattle, Washington in 1915, after his family had come from Taishan, in China’s Guangdong province. His mother died during a flu epidemic that hit Seattle during World War I. Because of this family tragedy, Chinn’s grandfather brought him back to Taishan in 1918. He attended the class of a “very strict” village teacher, and excelled in China’s highest art form: calligraphy (Chinn). This indicated he had the skill to become an artist, so, after receiving encouragement from an uncle, Chinn learned the methods of traditional brush painting.

2At that time, the Guangdong province was dominated by the “Lingnan School of Painting,” a style developed by Gao Jianfu and his brother Gao Qifeng, Chinese artists who had studied in Japan and portrayed natural subjects relatively realistically in loosely painted washes of vibrant watercolor and ink.[1] The Lingnan approach to Chinese painting spread to Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. These influences can be seen in the American Regionalist work of Andrew Chinn and Fay Chong, in their use of Lingnan ink painting skills, and their ability to synthesize Chinese traditions and new world subjects. After studying Chinese brushwork and learning about the Lingnan School, Chinn returned to Seattle in the late 1920s.

3Fay Chong was born in Guangzhou (Canton), also in the Guangdong province of China, in 1912, and immigrated with his family to Seattle a few years later. Chong went back to China twice, to study calligraphy in 1929 and, after befriending Andrew Chinn, to study brush painting in 1935.

Seattle

4Seattle is one of America’s most scenic cities, lying beside Puget Sound, between the Olympic Mountains and a string of national forests. The area’s natural environment has drawn artists for a long time. Seattle is also quite diverse, with especially large Native American and Asian American populations. Throughout the 20th century, Asian Americans attained prominence in Seattle’s art community, but worked to develop “their own artistic identity, rooted in their Asian heritage but adapted to the new life in America” (Nakane, “Facing” 55). Fay Chong and Andrew Chinn were active in the Chinese American community in Seattle’s International District, known today as the Chinatown-International District.

5When Chong and Chinn were in their late-teens a battle was waging in Seattle’s art world over how artists should “interpret visual reality” (Cumming 22–23). Conservative realist painters and pictorialist photographers—the Establishment—were on one side, and various small bands of avant-garde artists were on the other side. Some of the insurgents were local, like Kenneth Callahan and Mark Tobey, others were foreign-born. Three Japanese American oil painters Kenjiro Nomura, Kamekichi Tokita, and Takuichi Fujii, struggled valiantly, though ultimately unsuccessfully, “to synthesize [E]astern and [W]estern approaches to seeing reality” (Cumming 23). Chong and Chinn would have much more success with their watercolors a few years later.

Broadway High School, Seattle

6Fay Chong’s and Andrew Chinn’s lifelong friendship began on the tennis court; they played devotedly every morning on the playfield of Broadway High School. The diversity of its student body distinguished Broadway High, the first building specifically constructed as a high school in Seattle (Dorpat). Chong’s and Chinn’s classmates included Morris Graves, as well as George Tsutakawa, who later became one of America’s finest modernist sculptors. Tsutakawa’s early life mirrored Andrew Chinn’s—though born in Seattle, Tsutakawa spent eleven years of his youth in Japan. “[He] came to his Japanese schooling through the detour of being born in the United States. He came to his study of art in America through the detour of Japanese education” (Kingsbury, Tsutakawa 17). At that time, families often sent young Asian Americans to the family’s home country to complete their educations.

7Chong and Chinn naturally gravitated toward Tsutakawa, finding common ground, being artistic, “bicultural, bilingual, and older than other students” (Nakane, “Personalizing” 187). They all learned to make linoleum prints (along with Morris Graves), in the art classes of Hannah Jones and the progressive Matilda Piper, who showed her young students nude models. Chong, Chinn, and Tsutakawa were quite fond of these teachers, because they “encourage[ed] and nurture[ed] their special students, who had to cope with new adjustments each time they crossed the Pacific” (Nakane, “Facing” 67). Andrew Chinn happily recalled he was the “teacher’s pet” because he produced calligraphy with “such a beautiful hand” (Chinn). In his graduation year, Fay Chong supplied linoleum print illustrations for Broadway High School’s annual yearbook and Hannah Jones submitted his work to art competitions, effectively beginning Chong’s artistic career.

8Fay Chong’s earliest prints were monochromatic black linocuts; he later used multiple colors in single images, following the method of Japanese woodblock printing (Chong).[2] Likewise, Andrew Chinn’s watercolors from this period have affinities with both Japanese-style painting, or nihonga, and the Chinese Lingnan School of Painting, in their lack of outlining and use of contrasting layers of washes to suggest depth and spatial relationships.

The Chinese Art Club

9Asian American art clubs and associations sprung up in the 1920s in New York and all along the West Coast. For example, in 1924 Japanese immigrants Kyo Koike and Frank Kinishige formed the Seattle Camera Club, which was somewhat unique in that it had many non-Japanese members, published an impressive bilingual (Japanese and English) monthly journal named Notan, and attracted prominent speakers like Mark Tobey to its monthly meetings.

10Fay Chong and Andrew Chinn formed the Chinese Art Club in 1933, an informal group that met in a “shabby, little storefront studio” in the International District near the corner of Eight Avenue and Jackson Street (Cumming 154). The later expansion of Interstate Highway 5 destroyed the location. The Club’s original members were all Chinese Americans: Yippe Eng, a commercial painter, Howard Sheng Eng, an oil painter, and Larry Chinn, a watercolorist, but Chong and Andrew Chinn also welcomed and gave instruction to visitors Morris Graves, Kenneth Callahan, Guy Anderson, and William Cumming. The Club, which lasted four years, was an artistic hangout with the slogan “Art for Art’s Sake.” Cumming warmly remembered going to the Club to sketch nude models: “the model would back up to the oil heater in the back room on winter nights, leaving her rear end glowing scarlet for the next pose, while [Fay, Andrew] and I would sip tea or rice wine, [talking] about art and life” (Cumming 154–55).

11The Club’s first monthly show, at the Chinese School on Seventh Avenue and Weller Street, featured a linocut print by Chong and a watercolor of a local scene by Chinn (Nakane, “Personalizing” 187). Kenneth Callahan wrote a review in the December 3, 1933, Seattle Times, singling out Chong’s beautiful lines. Fay Chong was developing into a very accomplished and innovative printmaker.

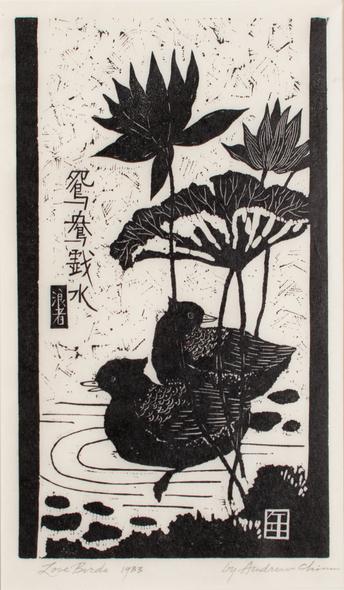

12At the same time, Andrew Chinn also produced a few linoleum prints of Chinese themes, such as flowers, pheasants, and lovebirds swimming in ponds (Fig. 1), but he did not like confining himself in the studio as much as Chong (Chinn). Chinn preferred taking a box of paints and a water jug outside to do nature studies (the plein air approach championed by 19th century French Impressionists, like Claude Monet). Although pleinairisme is not usually associated with Chinese art, as a child Chinn remembered seeing it practiced by a few “Chinese artists who went to study in France and Europe” (Chinn). Chinn convinced members of the Chinese Art Club and visitors to go painting outside with him. On one occasion, Guy Anderson took Chinn and Morris Graves out in his Model-T Ford to paint from nature; Chinn worked in watercolor, but Anderson and Graves preferred oil. In the studio the Club’s Chinese American members strictly followed traditional Chinese procedures, but outdoors they painted what they saw realistically (Chinn).

13In the watercolor West Lake, of 1935, Chinn depicted a local subject (a body of water inside Seattle’s city limits) with various Asian methods (Fig. 2). Chinn evoked black trees, seemingly floating in a blank field in the middle distance, by rolling the side of a brush vertically down the surface. Chinn included his signature ‘seal’ and a calligraphic description of the scene. Under Chinn’s direction, Chinese Art Club members, with varying degrees of skill, fused historical Chinese approaches and contemporary views of Seattle and its environs.

14Mark Tobey occasionally dropped in to the Chinese Art Club, toward the end of its existence, around 1937. Tobey was more than two decades older than Chinn and Chong and an established figure in Seattle’s art community. Fay Chong began visiting the art classes Tobey held at his home in the University District and continued studying with Tobey periodically for the next dozen years, a relationship that would prove pivotal to Chong’s later artistic development.

Regionalism

15When Fay Chong and Andrew Chinn were young there were no ‘Asian Americans;’ that term was not used until the 1960s (Chang and Johnson 9). In the 1930s and 1940s, the United States’ majority culture often considered people with Chinese, Japanese, or other Asian ancestries as simply foreign—and not part of the American mainstream. Yet Chong and Chinn strived to fashion “a distinctive American artistic profile that [ultimately] reflected the culture of both Asia and the West” (Chang and Johnson 10), and they did so in one of America’s most self-reflective periods.

16Following World War I and during the economic devastation of the Great Depression the United States went through a prolonged era of social and creative upheaval. The country’s attention turned inward in a widespread quest for a national cultural identity. “[Q]uestions of what ‘American’ art was supposed to be and who could be considered an ‘American’ artist were fiercely debated” (Wang 23). Writers, politicians, and art critics, in Art Digest and other periodicals, encouraged artists to distance themselves from European precedents and trends so they could create a distinctive home-grown American art, easily appreciated by ‘ordinary’ citizens. In larger cities, especially New York, social realists turned to depicting the working classes and urban life; in less-populated regions of the country artists banded together to paint rural landscapes and small-town life. Thus, Regionalism—the most-home-grown of US art movements—was born. At this time, in the far Northwest, Fay Chong and Andrew Chinn developed their unique form of West Coast Regionalism: portraying Seattle and its beautiful surrounding landscape using longstanding Asian artistic methods. They seized the opportunity to present the Northwest in an “unfamiliar way”—to envision America through “new eyes,” as Asian Americans (Chang xiii).

West Coast Regionalism and the Federal Art Project

17Regionalism on the West Coast, especially in California and Washington, was distinctive in two ways. First, it was dominated by watercolor specialists (rather than oil or tempera painters), and second, artists in California and Washington were strongly influenced by Asian art and ideas. In Los Angeles, for example, a new “California Watercolor Style” emerged, practiced by Millard Sheets, Phil Dike and others who grouped together at the Chouinard Art Institute. Critics often noted “Oriental” features in their landscapes, in particular Chinese and Japanese designs and color schemes (Anderson 36–37). The same was true in Northern California. Dong Kingman was a Chinese American born in Oakland in 1911. He went to Hong Kong to study Chinese brushwork before returning to Northern California to become the area’s premier watercolorist during the 1930s.

18Although Kingman masterfully blended Eastern expressive modes and American subjects, blended old techniques and new themes, he also questioned his personal identity: “I am Chinese when I paint trees and landscapes, but Western when I am painting buildings, ships or three-dimensional subjects” (qtd. in Cornell and Johnson 94). Asian American artists of the period often struggled to “reconcile the powerful emotional influence of their cultural ‘homeland’ (whether or not they were born there) with the creative energy and experimental openness of the United States” (Poon 5). Andrew Chinn and Fay Chong, Kingman’s almost exact contemporaries, experienced the same cultural tug-of-war.[3]

19The Depression era was a difficult time in Seattle. The stock market crash of 1929 initiated a decade-long economic downturn that put millions of Americans out of work. The federal government implemented make-work programs to help unemployed citizens in various trades. The Federal Art Project (FAP) sponsored by the Works Progress Administration put thousands of impoverished artists to work, helping them continue to develop their skills and collaborate on creative projects, while getting paid for their service. Fay Chong joined the FAP in 1938, after proving he was unemployed, incapable of finding other work, and almost at the point of starvation (Chong). Andrew Chinn joined the FAP in October 1941,[4] collecting an $85 monthly salary.[5]

20Many artists used the government art programs as stepping-stones to further their careers, including native Northwesterners Morris Graves—who helped Fay Chong get on the FAP—Kenneth Callahan, and Guy Anderson. Mark Tobey (who moved to Seattle in 1921) briefly joined the FAP in 1940. Graves, Callahan, Anderson, and Tobey later became the four core members of Abstract Expressionism’s Northwest School. Chong and Chinn used their FAP experiences to refine their professional identities and share their aesthetic interests with other artists. Indeed, it was during this time Graves, Callahan, Anderson, and Tobey developed their greatest interest in “the philosophies as well as the art of the Far East, [sowing] the seeds of the mystical quality that became identified with Northwest art” (Allan 10).

21At first, Chong produced only linoleum prints for the FAP. Then, in 1940, he started creating watercolors, working closely with Andrew Chinn. They also began experimenting with media, mixing various shades of Chinese ink with watercolors and painting exclusively with a Chinese brush on rice paper, which Chong remembered, was “fairly new [in Seattle] at the time” (Chong). They were both moving toward their mature styles, abstracting from manmade and natural motifs with energetic calligraphic brushwork, and spreading designs across their surfaces with colorful watery washes.[6]

22Like Dong Kingman, Andrew Chinn and Fay Chong painted a variety of subjects, including rural businesses and industrial structures, important features of a region’s environment and material culture. Chong’s watercolor Uncle Post’s Warehouse, for instance, shows the exterior of a decrepit sheet metal building, with a rusting “visible” gas pump and weathered furniture littering the surrounding junkyard (Fig. 3). The 1940s Ford pickup truck beside the warehouse also hints at the general date of Chong’s scene.

23Andrew Chinn’s work truly shines, though, in purer landscapes, studied either in one of Washington’s lush national forests or one of Seattle’s many urban retreats. “Nature nourished him in every way: emotionally, mentally, physically and spiritually” (Beers). In Seward Park (an area in southeast Seattle), Chinn delineates tree shadows and the edges of the hilly terrain with needle-thin lines of Chinese ink, but delicately feathers the brushwork when suggesting birch tree leaves softly waving under a typically overcast Northwestern sky (Fig. 4).

24Chong and Chinn’s watercolors are complex and subtle fusions of traditional techniques and new subjects, mixtures of old Eastern culture and a new Western environment. As a result, the artists and their artworks are difficult to define. The Lingnan School of Chinese painting was a profound influence, and the artists were late contributors to that movement. Alternatively, because of their subjects, Chong and Chinn were also important innovators in the broad development of Chinese painting, or guóhuà, in America, where many of the leading innovations in 20th century ‘Chinese’ painting were developed (Cornell and Johnson 11). Chong and Chinn continued to refine their watercolor style for the remainder of their lives.

25The relevance of the indigenous Regionalist movement began to wane during and immediately after World War II. “The war experience forced many American artists into a spiritual revolution, transforming them from painters of the local scene into seekers for a deeper meaning and significance to life” (Anderson 62). Modernist art, or abstract trends, began to take center stage, which affected Chong and Chinn in different ways. Although the FAP operated until June 1943, the project began to wind down a couple of years earlier. Fay Chong left to join a naval architectural firm, and then worked as an illustrator at Boeing Co. Andrew Chinn also went to work for Boeing, which affected his personal artistic approach somewhat,[7] and then was a technical illustrator at Sand Point Naval Base and Bremerton Navy Yard.

The Northwest School

26Andrew Chinn and Fay Chong were not only significant members of Seattle’s Asian American artists’ community and important Regionalist watercolor painters; they were also closely associated with the Northwest School, which began in the 1930s as a subgenre of West Coast Regionalism but grew, during the 1940s and 1950s, into a vital variation of the Abstract Expressionist movement. The core members or “big four” of the movement—Guy Anderson, Kenneth Callahan, Morris Graves, and Mark Tobey—had all been unofficial members of Chong’s and Chinn’s Chinese Art Club and worked with Fay Chong and Andrew Chinn on the FAP project.[8]

27The big four had already developed their characteristic styles by the mid-1940s (Tsutakawa 18), but they made their collective mark in New York’s art gallery scene in the early-1950s. They became national celebrities in 1953, when Life magazine published an article entitled “Mystic Painters of the Northwest.”[9] The article praised their conceptualized studies of Washington’s natural environment and infusion of Asian artistic processes, but failed to mention Chong or Chinn.

28The standard myth of the Northwest School, which was established by the Life article, is that Tobey, Graves, Callahan, and Anderson joined together in a search for “a universal language of form” that would speak to many, seemingly disparate cultures, and they were committed to expressing a “transcendental spirituality” that could be perceived in nature (Allan 24). Tobey, Graves, Callahan, and Anderson actually had varied interests (including Native American culture and European modern art), but what really made them stand out was their shared preoccupation with all things Asian.[10] Many Americans and Europeans in the post-World War II period were strongly attracted to Far Eastern mysticism and Zen Buddhist philosophy, and, in the arts, to Zen’s relationship to Japanese Sumi painting and calligraphy.[11] On the East Coast and in Europe, the Northwest School’s Asian qualities were most fascinating and desirable (Tsutakawa 18).

29The movement’s official roster, however, was always far too limited. Although they were all Caucasian, American-born artists, the big four derived their abstracted natural allusions, calligraphic brushwork, and even their emphasis on the “spiritual dimension” from Asian philosophy and art (Allan 10–11). Yet, artists with actual Asian heritages who also lived in the Northwest and shared many of the same interests have always been relegated to the periphery of the Northwest School’s inner circle, including Chinese American Fay Chong, his Japanese American classmate George Tsutakawa, and Japanese immigrants Kamekichi Tokita, Kenjiro Nomura, and Paul Horiuchi. Writers have, in fact, conceded that “quite a few active and influential artists, some of whom were associated with the central four, were not included in the original ‘school,’ [but] a tradition was established. Long since eclipsed, it is so ingrained in history that references to it, usually as a point of comparison, continue to be commonly used and understood” (Allan 11). It is time to challenge this tradition.[12]

30Mark Tobey studied Chinese calligraphy with T’eng K’uei, a Chinese exchange student at the University of Washington during the early 1920s. T’eng K’uei was to Mark Tobey what Fay Chong and Andrew Chinn were to Morris Graves, Kenneth Callahan, and Guy Anderson: a Chinese artist able and willing to transfer his knowledge of Eastern techniques to a Western colleague.[13] Tobey visited T’eng K’uei in Shanghai in 1934, and soon thereafter began his popular ‘white writing’ phase, in which he referred directly to Asian calligraphy. These paintings deeply influenced many progressive artists in Seattle.

31Andrew Chinn, however, did not sense an authentic Chinese quality in Tobey’s white writing and could not see the “mystic” spirituality that art critics described in Tobey’s art:

To me, it didn’t make much sense, because the Chinese writing [is] about power, [its] about thin and thick strokes, but with his white lines [there’s no] Chinese influence. There’s no variation in the strokes, and there’s no power. I don’t understand it, but certainly I don’t see the influence. [T]o me it’s highly decorative, you know. Millions of dots, a million strokes is highly decorative, see. (Chinn)

32Andrew Chinn was a close friend to Morris Graves, his high school classmate, for many years. Chinn remember Graves as “a very good entertainer,” who came to parties at the Chinese Art Club and amused everyone by telling jokes and dancing in a comical, twisting, contorted way (Chinn). However, Chinn also thought Graves’ work could be superficial. Chinn was well-versed in Asian iconography and he often depicted symbolic Chinese subjects like pheasants (the bird of prosperity) and lilies (emblematic of love and unity). Graves also represented symbolic plants and animals. Chinn remembered Graves checking out books about Chinese art history from the library during his formative years, and using pictures of bronze incense burners and wine containers for his paintings. Chinn considered the Chinese motifs in Graves’ work, like teacups, to be stereotypical, and did not sense a true Chinese quality in his formal or philosophical content (Chinn).

33Andrew Chinn thought it was a “very good question” why one group of artists who were influenced by Asian culture—Tobey, Graves, Callahan, and Anderson—became very famous, while another group of artists of Asian descent producing similar art were relegated to the margins. Chinn speculated that critical support was an important factor, but luck also played a role. “[I] play mahjong [a Chinese game of chance]: You gotta be good and you gotta also be lucky, too,” he said (Chinn).

34Tobey, Graves, Callahan, and Anderson were fortunate to have important supporters. The enthusiastic backing of Seattle’s museum curators (at the Seattle Art Museum, Henry Art Gallery, and Frye Art Museum) and gallery owners (including Zoe Dusanne and Otto Seligman) helped set the Northwest School’s core members apart from their likeminded friends, with favorable publicity and assistance in obtaining lucrative prizes. Richard Fuller, the director of the Seattle Art Museum, aided Graves (in 1946), Callahan (1954),[14] and Tobey (1956) in winning Guggenheim awards, and the efforts and contacts of Seattle gallery director Zoe Dusanne, one of the big four’s greatest promoters, resulted in the 1953 Life magazine article (Becker and Long). Fay Chong and Andrew Chinn never enjoyed such support, but if they had perhaps they would not be so easy to overlook today.

Later Legacies

35The standard myth of the Northwest School fits nicely into one of the larger narratives of American art in the 1950s, in which artists were said to have recoiled from the horrors of war and sought to reflect on “deeper meanings” and life’s spiritual significance (Anderson), often through abstract or abstracted modernist art. This new cultural climate impacted Fay Chong’s and Andrew Chinn’s careers in different ways. Chinn steadfastly devoted himself to a fusion of traditional Chinese techniques and Western realism, but increasingly worked in relative obscurity. Chong instead incorporated abstract, modernist elements in his work, and, as a result, remained relevant in the minds of critics for a longer period.

Andrew Chinn

36Between 1940 and 1960, the Seattle Art Museum’s Northwest Annual exhibitions regularly accepted Andrew Chinn’s watercolors, which usually depicted trees, crooked streams, and rock-strewn mountains. The choice of popular natural and local subjects was strategic on Chinn’s part as he knew they often won exhibition prizes (Chinn). In many of the later Northwest Annual exhibitions, however, as modern artists began to garner the most attention, Chinn began feeling like an outsider because of his realistic techniques (Chinn).

37Although his fellow artists and students respected Andrew Chinn, art critics did not always understand or appreciate his work, and this never improved. Critics greeted Chinn’s first solo exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum in 1942, featuring his characteristic Chinese-styled landscapes, with a limited, lukewarm response. “It was too early,” Chinn explained. Likewise, the local press did not praise his solo show at the Frye Art Museum in 1953, the same year Life magazine was introducing the “big four” to the world. “[A]t the time, the person who writes for the [Seattle] Times was the university type, you know, and [didn’t] think much about the conservative painting,” Chinn said. Perhaps critics did not embrace Chinn in 1942 because he had an Asian mode of expression, which was not appealing to many people in the ethnocentric climate of the Depression and World War II eras, and perhaps they did not embrace him in 1953, when Abstract Expressionism was on the rise, because of his realistic style. Art critics may have been unable to perceive or appreciate the subtle synthesis of elements in Chinn’s work, or perhaps it was something worse. Critics often neglected Asian American artists in the early and mid-20th century, in part, because Asian Americans, like “other marginalized racial groups, commanded little respect from any quarter of mainstream America, [which calls into question] how and who determines what is ‘art’ and who is an ‘artist’ worth studying” (Chang ix–x). Chinn, however, did not feel pressured to follow the new trends.

Because, you see, I paint for self-satisfaction. That’s the first thing in my mind. I don’t give a darn how they paint, I don’t. Self-satisfaction, that’s what I want. [Some modern art was good; some] I didn’t think much of. To me there’s a lot of gadgets, you know. You use it for a few years, and then that’s it. But the conservative type, they’ve always come back. (Chinn)

38Andrew Chinn taught a Chinese manner of watercolor painting, in his home and at a Seattle community college, from 1945 until his death from heart failure in 1996. Artist and educator Jess Cauthorn called Chinn “the last of the first vanguard of Asian-American artists. He was able to keep a high level of Orientalism in his work, resisting the trend to too much Western influence” (Beers). And today Chinn’s words still ring true. Collectors and art historians have, indeed, recently showed renewed interest in conservative, or traditional, Chinese art (and in Andrew Chinn).

Fay Chong

39Chinn speculated Fay Chong’s friendly, open-minded personality had a part in his ability to accommodate changing trends in the art world. “I am more traditional in my art”, Chinn said, “but Fay was more American in that he was always open to contemporary things” (Lau).

40Chong studied with Mark Tobey, at Tobey’s home in Seattle’s University District, from 1939 through the mid-1950s, and he developed a new abstract style that had much in common with other Northwest School painters. He continued, however, to make Regionalist watercolors alongside his more abstract work. For example in Mt. Vernon, Washington, a landscape of the early-1950s, Chong closely observed the countryside, which he subtly portrayed with a balance of black ink and watercolor earth tones (Fig. 5). Jagged, light, calligraphic strokes emphasize meaningful details, like the bare tree on the right or the corners of the rustic homes, while swathes of luscious watercolor applied across the paper with an ink brush unify the composition. Blurry, distant horizons suggest a deeply receding panorama. Chong’s more modern work also incorporated Chinese elements.

41In Cliff Formations No. 2, of 1960, he used a rhythmic pattern of vertical, horizontal, and diagonal calligraphic marks to suggest a vast Western canyon. Chong’s dynamic Calligraphic Lines No. 1 is similar (Fig. 6). It seems like a simple homage to Tobey’s ‘white writing’—and it does belong to the Northwest School of art. However, the blending of Chinese ink and Western watercolor, of Chinese writing and a Western all-over abstract composition, give the painting a special aesthetic mix that only an Asian American artist at that time and place could have produced. Such works led one writer to call Chong “an Oriental Feininger” (Anne Todd qtd. in Kangas 6), referring to Lyonel Feininger, the German American Expressionist who also reduced natural phenomena to linear, abstract impressions.

42Fay Chong downplayed his Asian heritage later in life—perhaps hoping to transcend any limitations others might impose on his art. “As for me, I am not trying to translate in my language of painting the oriental heritage, the essence from the traditional past. […] Simplicity and energy are my destination.” Chong said in the 1960s (Lau). Chong’s statement echoed the sentiments of many non-Asian modern artists of his generation. Jackson Pollock (who was born the same year as Chong), for instance, once said: “The modern artist […] is working and expressing an inner world—in other words expressing the energy, the motion and the other inner forces” (qtd. in Karmel 21).

43Although their art developed differently, Andrew Chinn and Fay Chong remained close friends until Chong’s sudden death from a stroke in 1973, aged 61. They both continued “painting away all the time. [But Chong] went on his own style, and [I] went in my style,” Chinn said. “Fay was a gentleman, always a gentleman. [He didn’t] say too much, but he had his convictions, too. He knew what he saying every time. See. And we stayed very good friends” (Chinn).

Conclusion

44Andrew Chinn and Fay Chong must come out of the shadows so the academic community can reassess what they added to Regionalism and Abstract Expressionism and general audiences can enjoy their remarkable artworks. The watercolors they produced in the 1930s and 1940s fused very old Asian techniques with new Northwestern American topics, and deserve a place of honor within the West Coast Regionalist movement. Chinn and Chong contributed to the Northwest School of Abstract Expressionism, Chinn by introducing the core members to Asian techniques and Chong as a significant member of the movement while studying with Mark Tobey. Better-known contemporaries and colleagues should not eclipse Fay Chong and Andrew Chinn. On the contrary, we should acknowledge them for what they were: Asian American masters of American art.

Notes

[1] During the Meiji period (1868–1912), the scholar Okakura Kakuzō, and others, called on young Japanese painters to preserve traditional Japanese techniques, which Western modernism seemed to threaten. In response, some young artists synthesized Japanese traditions and Western realist methods in depictions of contemporary subjects, an East-West blend called nihonga. The Gao brothers were strongly influenced by nihonga when they left the Guangdong province to study in Japan in 1906–08. When the Gaos returned to China they established the Spring Awakening Art Academy in Canton, where they developed a new Chinese variation of nihonga, the “Lingnan School.”

[2] Nihonga influenced many Asian American printmakers along the West Coast during the 1920s and 1930s, including the visionary Japanese American woodcut master Teikichi Hikoyama (1884–1957), who worked in California.

[3] Kingman worked for the Federal Art Project in San Francisco and Fay Chong may have met Kingman during this period. Chong described a trip he took to San Francisco during the late-1930s, “[D]uring one of the weekends we drove down there to San Francisco–Bill Cumming, Lubin [Petric], and I. […] We drove down–it was just after sketch class–for the fun of it, and we visited the art project down there” (Chong).

[4] Chinn joined the FAP just weeks before the United States entered World War II. China and the United States were allies in World War II and fought together against Japan in the China Burma India Theater. Chinese American artists were treated much better than their Japanese American counterparts, many of whom were forced to live in internment camps. Chinn and Chong’s inclusion in the government art programs may have reflected a relatively favorable climate for Chinese Americans based upon unfolding political and military events. “World War II marked a turning point for Asian American history. When the United States declared war against Japan on December 8, 1941, one day after Japan bombed Honolulu, the government’s attitudes toward the various Asian groups changed. No longer viewed as a devious, infiltrating ‘Yellow Peril,’ Chinese were now staunch supporters of democracy. China was an ally fighting against Japan [President] Roosevelt signed the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Acts on December 7, 1943. The repeal permitted Chinese to naturalize for US citizenship and implemented an annual immigration quota system” (Poon 7).

[5] The FAP estimated in 1936 that more than half of American artists could qualify for public assistance (“Art Becomes an Industry”).

[6] Chong and Chinn’s watercolors from this period feature a beautiful tension between energetic lines and washy color. Chong recalled his own motivations, “I feel that the Orientals stress so much on strength and energy in their work, and the strokes and lines give it energy more than a wash painting” (Lau).

[7] As a technical draftsman at Boeing Chinn studied isometrics, and in his free time began incorporating Western-style receding perspectives into his watercolors. Thereafter, Chinn’s images appear more volumetric and less delicately hazy (‘less Lingnan’).

[8] Graves and Tobey also frequently visited George Tsutakawa’s family store, a gathering place for Tsutakawa’s many Asian America artist friends (Poon 42).

[9] The term ‘mysticism,’ a vague catch-all suggesting a fusion of Asian and Western forms and philosophies, was used to describe Morris Graves’ work in the mid-1940s (Kingsbury, Art 58), shortly after he worked with Chinn and Chong on the FAP project.

[10] Kenneth Callahan visited Asia in 1927 and Morris Graves traveled to Asia in 1928 and 1930. “[Graves] visited local Buddhist temples in Seattle” and studied “Zen Buddhism, the tea ceremony Noh theater, and the thinking of [Ernest] Fenollosa in the later 1930s,” when he was close with Fay Chong and Andrew Chinn (Nakane, “Facing” 68–69).

[11] Recently, art historians have begun to pay more attention to Asian influences on the Northwest School, notably in Ament’s Iridescent Light: The Emergence of Northwestern Art.

[12] The blending of Eastern traditions and Western subjects and styles went in both directions. Artists with Asian heritages—like Fay Chong and Andrew Chinn—made great contributions to Regionalism (and, in Chong’s case, to abstraction) and non-Asian artists—like Morris Graves and Mark Tobey—made great contributions to the “exciting international synthesis” (Chang and Johnson 11).

[13] “How have artists such as T’eng K’uei been creative agents of this influence? How did they actively explore aesthetic interaction? In what ways have Asian American artists themselves been cultural translators, transmitters, or interpretors?” (Chang xiii–xiv).

[14] Fuller also appointed Kenneth Callahan a part-time curator at the Seattle Art Museum in 1934, a position he held for 20 years.

Works Cited

Allan, Lois. Contemporary Art in the Northwest. Roseville East: Craftsman, 1995. Print.

Ament, Deloris Tarzan. Iridescent Light: The Emergence of Northwest Art. Seattle: U of Washington P, 2002. Print.

Anderson, Susan M. Regionalism: The California View, Watercolors, 1923–1945. Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1988. Print.

“Art Becomes an Industry; Sales Beginning to Climb.” Seattle Daily Times. 13 Oct. 1936: 35. Print.

Becker, Paula, and Priscilla Long. “Life Magazine Sheds Limelight on Northwest School Painters on September 28, 1953.” History Link. 2 Mar. 2003, Web. 29 Nov. 2016. n. pag.

Beers, Carole. “Andrew Chinn, 80, Painter of Nature, Art Teacher.” Seattle Times. 16 Jan. 1996: C1. Print.

Callahan, Kenneth. “Chinese Art Work Shown.” Seattle Times. 3 Dec. 1933: 33. Print.

Chang, Gordon H. “Emerging from the Shadows, Forward: The Visual Arts and Asian American History.” Asian American Art: A History, 1850–1970. Ed. Gordon H. Chang, Mark Dean Johnson, and Paul J. Karlstrom. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2008. ix–xv. Print.

Chang, Gordon H., and Mark Dean Johnson. “Introduction.” Asian American Modern Art: Shifting Currents, 1900–1970. Ed. Daniell Cornell and Mark Dean Johnson. Berkeley: U of California P, 2008. 9–15. Print.

Chinn, Andrew. “Oral History Interview with Andrew Chinn, 9 August 1991.” By Matthew Kangas. Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. 2010. Web. 27 Mar. 2017.

Chong, Fay. “Oral History Interview with Fay Chong, 14–20 February 1965.” By Dorothy Bestor. Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. 2010. Web. 27 Mar. 2017.

Cornell, Daniell, and Mark Dean Johnson, eds. Asian American Modern Art: Shifting Currents, 1900–1970. Berkeley : U of California P, 2008. Print.

Cumming, William. Sketchbook: A Memoir of the 1930s and the Northwest School. Seattle: U of Washington P, 2005. Print.

Dorpat, Paul. “Now and Then: Broadway High School.” Seattle Times: Pacific Northwest Magazine. 17 Apr. 1994, 2. Print.

Kangas, Matthew. “East Looks West: Four Asian American Modernists.” International Examiner. 15 June 1986 Print. n. pag.

Karmel, Pepe. Jackson Pollock: Interviews, Articles, and Reviews. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1990. Print.

Kingsbury, Martha. Art of the Pacific Northwest from the 1930s to the Present. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1974. Print.

—. George Tsutakawa. Seattle: U of Washington P, 1990. Print.

Lau, Alan Chong. “Fay Chong: ‘I am more articulate with the brush than with the pen.’” International Examiner. 15 Apr. 1990. Web. 5 Apr. 2017.

Nakane, Kazuko. “Facing the Pacific: Asian American Artists in Seattle, 1900–1970.” Asian American Art: A History, 1850–1970. Ed. Gordon H. Chang, Mark Dean Johnson, and Paul J. Karlstrom. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2008. 55–82. Print

—. “Personalizing the Abstract: Asian American Artists in Seattle.” Asian Traditions Modern Expressions: Asian American Artists and Abstraction, 1945–1970. Ed. Jeffrey Wechsler. New York: Abrams, 1997. 186–89. Print.

“Mystic Painters of the Northwest.” Life 28 Sept. 1953: 84–90. Print.

Poon, Irene. Leading the Way: Asian American Artists of the Older Generation. Wenham: Gordon, 2002. Print.

Tsutakawa, George. They Painted from Their Hearts: Pioneer Asian American Artists. Seattle: U of Washington P, 1994. Print.

Wang, ShiPu. “Performing Diaspora: The Body and Identity in the Work of Asian American Artists.” Asian American Modern Art: Shifting Currents, 1900–1970. Ed. Gordon H. Chang and Mark Dean Johnson. Berkeley: U of California P, 2008. 23–30. Print.

Author

Dr. James W. Ellis is a Research Assistant Professor at Hong Kong Baptist University’s Academy of Visual Arts. Dr. Ellis was born in the United States, and earned his Ph.D. in Art History from Case Western Reserve University, after studying at Rice University (M.A.), and the University of Houston (B.A. with Honors). Thereafter, Dr. Ellis earned a J.D. from New York City’s Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, Yeshiva University, and practiced criminal and family law for several years before resuming his academic career, which has included undergraduate instruction and research. Dr. Ellis’s publications focus on 20th century art in the United States, particularly social realism and Asian-American modern art.

Suggested Citation