1Quite possibly the first book published by an African American through a commercial press, Robert Roberts’s The House Servant’s Directory is not only an important contribution to the ‘servant problem’ discussion. By virtue of both its mere publication and its contents, Roberts’s Directory raises the respectability of one of the few fields open to African Americans in the ‘free’ North, changing the image of service from an unskilled job to a meaningful profession with significant responsibilities.

© 2002 Division of Rare & Manuscript Collections, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

Used by permission.

Details of Roberts’s early life in Charleston, South Carolina are uncertain. Whether he was freeborn or not, he had firsthand knowledge of the debauchery that the system of slavery encouraged and was an active participant in the Abolitionist movement (Hodges xiv–xv). In prefiguring later calls for fundamentally changing our understanding of service, Roberts proffers a definition of professionalism that remains largely applicable today, illustrating the self-determination engendered by a belief in the efficacy of hard work. In cleverly addressing both employers and servants, Roberts presents a vision of shared enterprise and mutual respect as necessary to the successful household—and republic.

2As Inez Goodman noted before beginning her own experiment in domestic service, “there is nothing on that Woman’s Page but growls and groans over servants” (“Ten Weeks” 2459).[1] Many mistresses are confounded by the fact that young women prefer the shops and factories to working in their homes. Even Goodman believes that the “American girl seeking a livelihood ought to find her most comfortable and profitable opening in domestic service” (“Nine-Hour Day” 397). Notably absent from the conversation, however, is the perspective of the servants themselves. As one anonymous “girl” with twenty years of experience in domestic service responded to her brother’s suggestion that she publish her own account: “I am sorry, but under present conditions it is impossible for me to write anything on any subject. This may seem incredible, but it will not be when I tell you that from six a.m. to eight p.m. I don’t get time to write so much as a postal card. After the day is over I am too tired, confused and nervous to do anything except look over the paper and go to bed” (“Servant Girl’s Letter” 36). In addition to the lack of time, servants often feared negative repercussions resulting from their honesty (Dudden 237–38, Salmon ix). Of the few servants who did share their experiences, most had a greater sense of security and of their own rights that came from being white and comparatively privileged.

3Most famous among these middle-class servants was Louisa May Alcott who writes extensively about her experiences in “How I Went Out to Service” (1874), but also comments on the servant problem throughout her fiction, including Little Women and Work.[2] Alcott’s work argues that the solution to the ‘servant problem’ is a return to the earlier model of ‘help’ prominent in post-Revolutionary America, in which young girls worked in their neighbors’ homes as a kind of apprenticeship before leaving to get married and manage homes of their own. By treating one’s servants as friends and relaxing rather than solidifying the social barriers between employers and employees, Alcott believed domestic service would once again be seen as an attractive, respectable means of supporting oneself.

4Others also present domestic service as an apprenticeship, though without the elimination of class distinctions advocated by Alcott. As Marion Harland writes in the Independent, “Each of these women hopes and means to have her husband and home in God’s good time. She will have to cook her husband’s meals, take care of his house and bring up his children. She will be a better wife, housekeeper and mother for the apprenticeship to be had for the seeking in any one of a thousand homes in town and country” (2292). As is often the case, a paternalistic (or maternalistic) undertone is apparent. “It is hardly possible that a girl, willing to learn and ready of apprehension, should be, for years, in daily intercourse with women of refinement and educations without catching their tone, and to some extent imbibing their principles and opinions.” This “refining environment” in which servants work will ultimately result in their being superior to the factory and shop girls (2292). In response to the complaints from servants over their lack of free time and their inability to receive their own visitors, Harland tells the sad tale of her own “pretty Margaret” who left to find work in a factory, shop, or work-room, only to be seen later in questionable male company and smelling of whisky. The mistresses of “unsophisticated girls” are at fault for being too indulgent rather than too strict (2293). According to Catharine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s popular guidebook of the period, The American Woman’s Home, refining one’s servants was a primary responsibility of the American housewife. They even refer to the middle and upper-class mistresses as “missionaries” whose vocation it is “to form good wives and mothers for the republic” (326–27). Margaret Sangster, another contributor to the Independent, echoes the “missionary” role of housewives, arguing that through the “magic of love” they can govern and guide the young servant girls in their homes (2605–06).

5Not all responses to the “servant problem” advocate a more “familial” relationship between mistresses and servants, however. Although Inez Goodman does instruct mistresses to “Look your maid in the face the next time you go into the kitchen, look as if she were your daughter,” she also prescribes definite working hours, first ten and then in a follow-up essay, nine (“Ten Weeks” 2463). “The whole history of the labor movement shows a slow but steady shortening of the hours of labor in every trade and occupation. Is it expected that household servants will continue forever to work fourteen hours a day when their sisters in shops and factories work less than fifty hours a week?” (“Nine-Hour Day” 398). Along with regular, reduced hours, Goodman also opens the door to servants living out—as in most other occupations—therefore giving them full possession of the other fourteen or fifteen hours to do as they please. “If we are to have intelligent service in the kitchen we must make the position one that an intelligent girl will consent to occupy” (399). Treating domestic service as a profession, Goodman argues, is the primary means to that end.

6Although Goodman seeks to standardize the relationship between mistresses and servants, she remains nostalgic about ‘advising’ her own maid on her penmanship and sewing, and having her join the family in prayer. Lillian Pettengill argues rather for a complete professionalization of the relationship. Indeed, she rejects one employer’s attempts to be on more sociable terms, as she recognizes that in the presence of guests, things would have to be altered. “[M]y place is out here, and I think I’d better stay in it always since I must sometimes. It’s simpler” (105). This disappoints her employer, who wants the companionship and is “eager for a new interest” but who also believes “a really nice girl wouldn’t think of sitting down with us when there was company” (106).

7Pettengill, like Goodman, was not born to a life of service. A graduate of Mount Holyoke, she initially moved to New York hoping to find work as a journalist. Though financial pressures contribute to her decision, she chooses domestic service specifically because she too is curious to find out why “respectable” American girls “will cheerfully starve and suffocate in a mill, factory or big department store, or live almost any other kind of life,” rather than turn to domestic service, despite the high demand evident in the papers (Pettengill v). She identifies five major areas of complaint among workers: 1) the social stigma, 2) the long and indefinite hours of work, 3) the lack of variety of work, which could be compensated for if not for 4) the lack of opportunity for a distinct home or social life, and 5) the lack of opportunity for “regular business promotion” (366). Seeing domestic service as a business is pivotal to solving the problem. The days of “help” belong to a simpler time, and as the shared work and companionship of that time have disappeared, so too should the expectations of patronizing employers and “filial” employees (384).

8Regular, fixed hours and set days off are a necessary first step. With fixed hours servants would be able to live in their own homes and enjoy their own company, coming to work in the morning and leaving in the evening. Of course, this necessitates some changes in the household. No longer having a housemaid always within call would require families to fix their own schedules, which Pettengill argues would be a benefit to all parties; “Besides, a dinner ordered at half-past six is a business engagement with the cook, and should be honoured as such” (370).[3] In providing for herself—with the fair equivalent in salary of her room and board—rather than being ‘cared for,’ the worker will gain both self-respect and the respect of others, and help erode the paternalistic notions promoted by Beecher, Stowe, and others, which were often used to legitimize restrictions on servants’ ‘free’ time.

9Having maids live out would result in some work falling to the family members, which Pettengill regards as beneficial to all. Sharing a small portion of the household labor will increase understanding and help to lift the social stigma attached to it. Despite her sense of class prejudice being even more deeply rooted than race prejudice, Pettengill notes that “professional toilers” in other fields respect one another for ability and accomplishment. “Lineage is but an accident, heirlooms and legacies a caprice of fortune; all men are brothers, rank is by individual worth, and work a high privilege” (372). Anything else would be undemocratic and therefore un-American. The solution, as her title suggests, is to rank domestic servants among “professional toilers.” As such, Pettengill raises the possibility of training schools for domestic workers and a union which could certify workers of high quality, act as a placement agency, and offer “friendly arbitration” in matters of dispute between employers and employees (393).

10The outstanding grievance for Pettengill to address is the lack of opportunity for promotion. Those who are ambitious and skilled are forced to promote themselves by moving from house to house—a chief complaint of many mistresses, who expect the personal devotion from their household staff common during the earlier period of “help” without the social equality on the other side. Larger, wealthier, more fully staffed homes allow for lighter work and the companionship of other domestic workers; they also allow for specialization, which brings better wages. Girls who begin as general maids can aspire to work their way up to these more attractive positions. This does put houses of more modest means at a disadvantage, which they must accept: “I trust I shall remember, the days of slavery being passed, that my girl, cook or other maid is not my property, and that she is entirely free to leave my employ for that of any other housekeeper who shall make it worth her while—as free as the wind that blows. Nor shall I blackguard the more fortunate woman who can offer superior attractions.” In subtly attacking the price fixing common among housekeepers in many communities, Pettengill shows how such practices undermine motivation and discourage the very kinds of talented workers mistresses claim to be seeking. Open markets and an understanding that “Keeping house with a hired helper is the conduct of important business” will both incentivize the workers and engender reform among housekeepers (394–95).

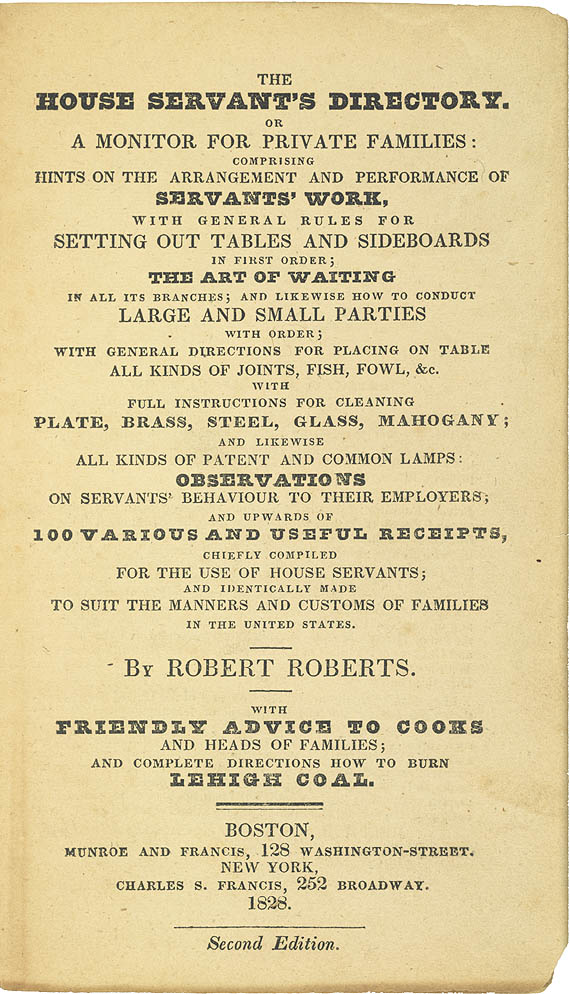

11Pettengill’s insistence on an absolute business model as the solution to the “servant problem” appears radical enough at the turn of the twentieth century. Yet Robert Roberts argued, albeit more subtly and deferentially, for much the same approach back in 1827 at the beginning of the shift from help to service. Roberts’s cleverness is evident before opening the book. Referred to as The House Servant’s Directory, the full title reveals his dual purpose: Or a Monitor for Private Families: Comprising Hints on the Arrangement and Performance of Servants’ Work. The original title page goes on to list a number of subjects covered—from the art of waiting at table to the proper cleaning of mahogany—and ends with a reminder that the text is “chiefly compiled for the use of House Servants.” But although he begins his introduction by addressing himself to his “young friends Joseph and David, as they are now about entering into gentlemen’s service,” a close reading of Roberts’s text reveals that he is at least as determined to advise the “gentlemen” whom they may serve (lvi).

12Roberts’s introduction emphasizes the “honorableness” and dignity of labor, no matter what that labor is: “the various stations of life are appointed by that Supreme Being, who is the giver of all goodness; therefore every station that he allows us to fulfil [sic], is useful and honorable in their different degrees” (lvii). The historical and Biblical examples to which he has recourse show domestic servants in particular entrusted with “matters of great importance,” including Joseph from the Book of Genesis. Roberts also cites the Biblical story of Jacob to show that even when an employer behaves unjustly, “the Lord blessed the honest and upright servant” (lix). Labor is, as Roberts later argues, one of the responsibilities of freedom, and should be viewed as a great source of pride: “[I]t is the fair price of independence, which all wish for, but none without it can hope for: only a fool or a madman will be so silly or so crazy, as to expect to reap, where he has been too idle to sow” (133). In her groundbreaking 1897 study on domestic service, Lucy Maynard Salmon cites de Tocqueville’s assessment that servants in America (free servants, that is) are not degraded by their work because it is freely chosen, unlike the servant “classes” into which one can be born in aristocratic countries (57). As Roberts clearly demonstrates, respect for oneself as well as respect from others stems from a thorough understanding of one’s chosen profession and a faithful execution of its duties, and the measure of the man comes through the quality of his chosen work—not his “station” nor, presumably, his race.[4] And as his outline of the various duties of the servant—particularly the male servant—will show, the property and indeed the lives of his employers depend upon him (53–54). This is a profession, therefore, requiring talent, training, and character; one that demands and also fosters manliness.

13The failure to see the role of servant as a profession has resulted in many untrained men entering the field without the proper knowledge of “several branches of their business.” This shortcoming compels the lady of the house to order them about continually, which in turn keeps the servants always in a “bustle” and their work incomplete (HSD lvi). As Roberts later writes, “there is nothing that looks so bad as to see a man in a bustle. […] He should always take hold of his work as if he understood it, and never seem to be agitated in the least” (48). Evident by the fussy tone of the repeated “bustle,” this also undercuts the manliness and respect Roberts wishes to attach to this profession, and, he is careful to point out, inconveniences the employer by constantly needing to oversee the employee and by rendering the employee inefficient. In his “Word to Heads of Families,” Roberts counsels that servants over the age of thirty are preferable. Before that age, the lack of experience and their “hope of something still better” leaves them restless and perhaps insufficiently motivated (142). In so arguing, however, Roberts also touts this as a job to which one must aspire, presumably with the kind of apprenticeships common to other professions that would give one the necessary experience. In the meantime, Roberts’s text can serve as an instructional manual with directions “to practise [sic] and study” for those young men who already have good positions without the proper training and as a reference guide for others (lvi).

14The most important training a servant must acquire is on setting up and managing a dinner party, and Roberts reminds his audience that it is no small task to do everything “in proper and systematical order.” Parties are of course a public presentation of the household to outsiders and reflect upon the host; they are also, however, an important opportunity for the servant: “It is a branch of a servant’s business wherein he can show more of his ability than in any thing else that he may have to encounter” (31). Having himself been hired away by former Massachusetts Governor Christopher Gore from one of Gore’s friends, Roberts knew the value of impressing not only one’s current but also potential future employers. Moreover, unlike much of the hard labor that is specifically performed outside of the view of the family, this represents an occasion to demonstrate one’s worth.[5]

15In his study of domestic service, Seven Days a Week, David M. Katzman notes that the “vocabulary of business, manufacturing, and commerce” becomes common in the discourse of reformers of the “servant problem” in the 1890s (251). Yet Roberts is already employing that language, repeating the word “business” three times in the opening paragraph to this section. The word “confusion” also appears in the paragraph three times, showing the result of a less-than-professional approach. “I have always found that one good servant that understands his business, can do more work in its proper order than three awkward ones, as they are chiefly in each other’s way, and this causes a great confusion in the course of dinner” (HSD 31–32). Attempting to economize with cheaper labor, in other words, will backfire. So will trying to get away with too few servants: “There are some families that think a servant ought to wait on eight or ten at dinner, but I tell them they are much mistaken; for this is too many for one man to wait upon, to do it to perfection; and especially if there are many changes” (32). This is a bold sentence. By appealing to the employer’s sense of propriety, efficiency, and necessity, Roberts asserts a kind of partnership with the employer, sharing his expertise and advice, while incidentally providing employment opportunities for his professional colleagues.

16When attended to, Roberts’s advice will rid the dining room of his dreaded “confusion” and “bustle.” The truly talented servant, however—the one called to his work rather than merely trained for it—can elevate his work above the merely proper to the artistic: “There are some old and experienced servants, that will set out their tables and side boards with such a degree of taste and neatness, that they will strike the eyes of every person who enters the room, with a pleasing sensation of elegance” (HSD 35). Although a reviewer of the second edition ridicules Roberts’s “notions of grandeur,” Roberts cautions that even the most beautiful and costly items can get lost in a disarrangement of objects (“House Servant’s Directory” 157). Far from the inflated sense of grandeur the reviewer sees, the servant with an instinct for what we might call staging is able to display his employer’s precious possessions to their best advantage, allowing guests to notice and appreciate them. Roberts’s use of the word “taste,” then, is in the Kantian sense of an innate perception of the aesthetic, raising service of this kind to a vocation requiring certain gifts.[6]

17As professional partners in running the household, both servants and their employers have functions they must perform. The servant has a duty to present a professional appearance. In addition to giving minute details about the kinds of suits and other clothing one should have for the various seasons and times of day and the different kinds of work, Roberts devotes particular attention to cleanliness. “There is no class of people to whom cleanliness of person and attire is of more importance than to servants in genteel families” (HSD 4). Certainly, the ladies and gentlemen of the household do not wish to have their meals served by slovenly or unclean persons. Equally important, however, is the sense of being engaged in an honorable profession such attention to detail promotes among the servants. Rising early and finishing the dirtiest work before the family is awake allows the servant time to look after himself, to wash and change his clothing so that he arrives in the dining room feeling and looking respectable, a credit to the family, certainly, but also “for his own credit.” Running about with dirty hands and clothes, on the other hand, foments the confusion and bustle to which Roberts is so averse, perhaps because of the emasculated image it conveys (3–4). Lillian Pettengill bristles at the prevalent attitude equating servants with children; for Roberts, avoiding behavior that supports this patronizing attitude by properly managing one’s work environment restores the dignity to the work and the worker.

18Not all in the work environment is in the servant’s full control, however, and he has an obligation once again to advise his employer on what is lacking. Roberts instructs: “Every servant should see that he has proper utensils to do his work with, as you cannot expect to do your work in proper order, if you have not the means to accomplish it with” (6–7). Lamps, for example, if not properly cared for, will not only give poor light but can become a hazard, filling a room with smoke; “But it is not always a servant’s fault, for, unless there is good oil, and plenty of it allowed to the man, it is impossible for them to burn well.” One of the first orders of business then, upon beginning work in a new home, is to inspect the lamps and if they are not in good order, “that is, if they are so bad that you cannot remedy them yourself,” to inform the employer so they can be sent out for repair (9). When addressing himself to cooks, Roberts cautions: “It will be to little purpose to procure good provisions, without you have proper utensils to prepare them in: the most expert artist cannot perform his work in a perfect manner without proper instruments; you cannot have neat work without nice tools, nor can you dress victuals well without an apparatus appropriate to the work required” (132). As the expert in the field—the artist—it is up to the employee to ask for what is required. The employee also needs to advise and indeed instruct employers, as Roberts did on the number of servants required per dinner guest, when more is demanded than can be accomplished:

Never undertake more work than you are quite certain you can do well: and if you are ordered to prepare a larger dinner than you think you can send up with ease and neatness, or to dress any dish you are unacquainted with, rather than run any risk of spoiling any thing, (for by one fault, you may perhaps lose all your credit) request your employer to let you have some help. They will acquit you for pleading guilty of inability, but if you make an attempt, and fail, they may vote it a capital offence. (135)

In setting reasonable expectations with the employer, the cook, like the servant managing the party in the dining room, appears knowledgeable and capable rather than incompetent and “confused.”

19The employer also has responsibilities to the cook: “The greatest care should be taken by the man of fashion, that his cook’s health be preserved” (144). Roberts stresses the need for cleanliness and proper ventilation in the construction of the kitchen. He also emphasizes the importance of proper lighting and of building the hearth where it will receive the most light. And while servants who waste the property and provisions of their employers are “wicked and dishonest” (61), the cook who has coal and butter “meted out to her” by the quart or the ounce, or who is expected to attend to other household tasks in addition to those of the kitchen, cannot perform her job adequately (145). As with hiring too few or too inexperienced servants, this form of economizing is ultimately detrimental.

20The most important aspect of a servant’s duty, according to Roberts, is at the end of the day when everyone else has retired: checking that all lamps and fires are extinguished and that all doors and windows are locked. “It is so great and important a part of your duty, that the lives and property of your employers depend on it” (53). As the manager of the household, which is surely how Roberts sees this role, it is the servant’s job to guard and protect the home and the family—a manly and weighty responsibility. Rather than the traditional hierarchy of servant and master, Roberts shows the employee as a stand-in for the head of the house, someone who performs the role of caretaker and guardian in his place. In responding to the equating of servants with children who should appreciate being well-provided for, Lillian Pettengill writes: “But the fullness of life is not in eating and drinking. […] The patriarchal idea as a basis for domestic service, though very pretty in antique setting, is in this age and land of the industrially free a glaring anachronism cradled in snobbery” (241). At the time of Roberts’s writing, however, the United States is still a pre-industrial nation, and as Roberts was painfully aware, far from entirely free. Rather than attack the patriarchal ideas directly, Roberts depicts them as out of place. Of course one would not trust a child with the responsibility for one’s life and property. It is less a matter of snobbery and prejudice than of logic. Employers must recognize the humanity and skills of their employees in order to entrust them with the management of their homes.[7]

21Although Roberts subtly rejects patriarchy as a basis for the relationship between employer and employee, he does argue that the role of patron comes with some responsibility for the health and well-being of “those who are dependent on them for their present, and often-times their eternal good” (HSD 141). Employers should have reasonable expectations and demands and be certain to praise as well as criticize calmly and fairly: “to cherish the desire of pleasing in them, you must show them that you are pleased” (142). When employees are sick, employers must remember that they are their “patron as well as their master” and not only temporarily release them from their duties but provide them with whatever medical treatment and attention or special nourishment they require. When it comes to female servants in particular, employers have a responsibility to pay “liberal wages” if they are genuinely interested in protecting and encouraging virtue. While supporting foundling hospitals and female penitentiaries has its place in philanthropic work, Roberts, in another bold moment, reminds his audience that “Charity should begin at home” and “prevention is preferable to cure,” highlighting the stinginess of many of these same donors for contributing to the need for such institutions (143–44).

22In addition to kindness from one’s employer, however, Roberts advises his fellow servants that their “greatest comfort” comes “in their behavior and conduct towards each other” (56). Living with others, as many accounts illustrate, can create tensions and conflicts; there is also professional jealousy and the mistaken belief that one can win favor with the employer by demeaning one’s co-workers. But servants can be a source of solace for one another, especially important in the absence of relatives or other friends. And like their patrons, they bear a certain amount of responsibility for both the present and future well-being of their “comrade servants”: “Take care and never do an injury to any servant’s character, for how easy they may be thrown out of bread through it, and perhaps led to greater evils” (58–59). Roberts does not imagine a union (like Pettengill) or a substitute family (like Alcott), but a professional and caring group of colleagues.[8] In keeping with his emphasis on the responsibility of freedom and the independence of the highly qualified worker, he also admonishes servants to look after themselves and plan for their futures by spending their money wisely and saving for the time when they are no longer able to work (63–64).

23Treatment of and behavior towards others persists as an important theme throughout the book and Roberts clearly indicates the professional consequences of our behavior. (Indeed, much of Roberts’s advice to his “young friends” on professional decorum is still relevant today.) His awareness of the need for external deference in many circumstances should not be mistaken for servility, however, but rather seen as an important strategy for advancement with implications beyond a single person or profession.

24In his advice to cooks, Roberts remarks that a good cook can quickly become a favorite domestic in the household. They should take care, however, to be kind and generous colleagues: “To be an agreeable companion in the kitchen, without compromising your duty to your patrons in the parlour, requires no small portion of good sense and good nature; in a word, you must ‘do as you would be done by.’ Act for, and speak of every body, as if they were present” (126). In addition to being the “Christian” thing to do, it is also the professional thing to do, and failure to follow this advice can have disastrous professional consequences. The cook, Roberts reminds us, is dependent upon the servants who wait at table and in the parlor to inform her of how her work is received, allowing her to adjust her cooking to suit the particular tastes of the family. Not only must she take care not to denigrate the work of others, but she should be modest about her own success: “[N]ever boast of [your master’s] approbations, for in proportion as you think you rise in his estimation—you will excite all the tricks that envy, hatred, and malice, and all uncharitableness, can suggest to your fellow-servants; every one of whom, if less diligent, or less favored than yourself will be your enemy” (125). Immodesty can also lead to over-confidence, which often results in less attentiveness and ultimately, less success. Indeed, too great a level of comfort can lead many servants into fatal errors of behavior.

25Roberts advises that all domestics should be “submissive and obedient to their employers” and their visitors (56). They should never attempt to engage in conversation unless spoken to first, “and then you should answer them in a polite manner, and in as few words as possible; for you must know that it is a very impertinent thing to strive to force a conversation on your superiors” (55). While today’s readers may find the idea of “submitting” to one’s “superiors” distasteful, the reality of nineteenth-century America for African American and later Irish domestic workers was if they wanted to remain employed by white middle and upper-class families, deference was a condition of that employment. Showing visitors one’s refined and pleasing manners was also an important marketing opportunity. As Roberts knew from his own personal experience, a visitor might be a prospective employer with a better position to offer.[9] “You should likewise be civil and polite to all visitants who come to the house, and treat them with as much respect as you would your own employers, for it is a great advantage to a servant, to have the good wishes of those ladies and gentlemen that visit where they live, because you may perhaps one day or other, have access to their good word, &c.” (56). At the very least, impressing visitors to the house could increase a servant’s value and conditions. As Graham Hodges has noted, even as black men left service for other fields, including their own entrepreneurial endeavors, their businesses “required interaction with whites, many of whom were capable of boorish racism” (xxxvi). Roberts’s advice on remaining calm and deferential—while allowing one’s skills to speak for themselves—was a source rather than an undermining of one’s dignity. It is also possible to see in Roberts’s advice, however, a clever strategy. As an active member of the Abolitionist movement, Roberts well knew that in order to abolish slavery and gain equal rights, whites—especially white men who could vote—needed to be convinced of the worthiness of both the cause in the abstract and of the African American race in particular.

26In admonishing his imagined protégé to “govern thy tongue and passions, when thou art angry with any person; for anger will hurt you more than injury,” Roberts has more in mind, I believe, than just the potential professional cost to the individual; indeed, in adding that one should “never to be a slave to passion”—surely a loaded phrase for a black man in 1827—Roberts evinces a keen awareness of how a person’s behavior, especially a person of color, could be used against him. The behavior of the individual or representative man could also impact other members of his community, for better or worse. “Always strive to relieve those who are in distress, if it is in your power, for the christian religion not only commands us to help our friends, but to relieve our greatest enemies; for so we shall make them our friends; and shall promote love, kindness, peace and good will among men. […] Virtue procures and preserves friendship, but vice produceth hatred and quarrels” (lx). Roberts’s calm, dignified persona was perhaps an important factor in his being elected Chairman of the Anti-Colonization meeting of the “colored citizens of Boston” in February, 1831, and the report of the proceedings he later published in the Liberator (March 12, 1831) supports a reading of his advice above as strategic. Convincing the “white citizens who had formed a State Society auxiliary to the American Colonization Society” as well as the “enlightened public” that so-called “re-colonization” to Africa projects were not only misguided but a violation of democratic and Christian ideals was a necessary step in converting enemies into friends and promoting the cause of freedom (42). As his report clearly indicates, Roberts’s ultimate goal is not only the abolishment of slavery but the granting of the full rights of citizenship.

27Roberts’s writing itself—like Frederick Douglass’s more than a decade later—stands as a testimony to his humanity; it is logical, erudite, and insistent. He begins with an outline of the Committee’s first responsibilities, which are to verify that the Massachusetts chapter of the American Colonization Society has indeed been formed and by whom. Once that has been clearly established, the body of the report is devoted to outlining the reasons—in the tradition of Jefferson’s “Declaration”—for their “disapprobation” (“A Voice from Boston” 42). In response to the belief that “Africa is our native country,” Roberts asks: “how can a man be born in two countries at the same time? Is not the position superficial to suppose that American born citizens are Africans?” Taking as fact that African-Americans born in the United States are citizens, Roberts then points out the numerous instances of black Americans who have traveled to African countries and fallen victim to native diseases precisely because they are foreign. With regards to the theory that establishing a colony on the coast of Africa would put an end to the slave trade, Roberts remarks: “We might as well argue, that a watchman in the city of Boston would prevent thievery in New-York, or any other place; or that the custom-house officers there would prevent goods being smuggled into any other port of the United States.” He further contends that though the disease of slavery is in America, rather than Africa, removing the slaves does nothing to prevent their being recaptured later; it is the slave market—not the enslaved people—which must be removed.[10] As for the alternate proposal that a colony for blacks be formed somewhere within the United States, Roberts reminds his readers of the recent treatment of Native Americans. As he well knows, such a colony would likely be a temporary step toward the real goal of removing African-Americans entirely from the country (in addition to the fact that “free people” ought to be able to “go where they please” without interference from others). To those men who have represented themselves as being “honest and benevolent” who are genuinely seeking a solution to the problem of slavery, Roberts offers two succinct options: “the removal of the free colored population from this country, or the acknowledgement of them as citizens. The former position must be acknowledged, on all sides, as a means of perpetuating slavery in our land; the latter, of abolishing it; consequently it may be seen who are for the well-being of their country.”

28Roberts reserves his harshest criticism in the report for members of the clergy who have supported the “clamorous, abusive and peace-disturbing” efforts of the Colonization Society:

And if your respectable body should not think your committee were going beyond the bounds of their duty, they would recommend the clerical order throughout the United States, who have had or who are having any thing to do with the deceptive scheme above alluded to, to read the 13th chapter of Ezekiel. Read it—read it—and understand it. Your committee would recommend those clergymen, who have not defiled their garments with the blood of the innocent, to read the 1st, 2nd, 11th and 12th verses of the 24th chapter of Proverbs. (“A Voice from Boston” 42)

Roberts further compares those clergymen who have used their positions to promote this “absurd idea” to their congregations to the false prophets and priests denounced by Jeremiah. As the Biblical passages he refers to suggest, they cannot be genuine Christians and support this agenda. Roberts concludes on a positive note, commending and thanking those “whose independence of mind and correct views of the rights of men have led them so fearlessly to speak in favor of our cause;” the very rights indeed “for which their veteran fathers struggled in the revolution”—a subtle but pointed reminder that slavery is at odds with American ideals.

29Hardly the work of one who saw himself as subservient, when read together with The House Servant’s Directory Roberts’s report emphasizes his method of carving out one’s place and making oneself necessary. The logical and persuasive orator/writer was clearly someone ably fulfilling the demands of citizenship to which he was laying claim, just as the servant who had proven himself expert in the field of household management deserved the respect and recognition of those he served. Roberts’s emphasis on continuing education throughout the Directory—along with his later efforts to help found a manual labor college for young black men[11]—sets forth a philosophy that anticipates Booker T. Washington: if you begin by making the worth of your labor felt, you will ultimately convince those around you of the worth of your person and your contributions to your employer (and the republic) will be properly valued and welcomed.

30Roberts counsels his young readers to “embrace every opportunity of learning any thing which may be useful” (HSD 127) and “depend upon it you cannot learn too much of every thing in the least connected with service” (107). Even if they are not given the opportunity in their current positions to employ all of their skills, they might make use of their knowledge in future endeavors including, perhaps, in their own homes and families. And a “complete and full knowledge of the business would do you no harm.” But, he cautions, they must not be intrusive, either as they seek out this knowledge, or after they have acquired it: “[L]et your ‘light be hid under a bushel,’ always ready for modest use, if required” (107).

31As examples from his own work attest, Roberts, it seems, was always alert to occasions for professional development. Following his directions for “Brushing and Cleaning Gentlemen’s Hats,” Roberts states: “I have received these instructions myself, from one of the best hat manufacturers in London” (20). Similarly, his guidelines for cleaning mirrors conclude with the assurance that “[t]he author had this receipt from one of the largest looking glass manufacturers in London” (77). But even servants without the opportunity to travel or access to such notable experts could continue to improve their skills by paying attention, and it is striking how many times the word “study” appears in the Directory: “In setting out your sideboard and sidetable you should always study convenience and elegance, in putting your things on, and study to have plenty of every thing, that you need not have to leave the room during the course of dinner” (38); “Make it your study to put every thing on with taste, and as though you had a design for taste and ingenuity” (52). Even more important than access to experts in London is the ability to read the particular tastes of one’s employer: “always study to give general satisfaction to those you serve” (26). And performing one’s work skillfully was an important factor in fostering the manliness Roberts so valued: “a lady should not want to be troubled to look after these things, if she has a man that is capable of his business. You should therefore make it your chief study to keep every thing in good order that is under your care and influence” (24–25). The proficient and adept servant could be that man. While Lillian Pettengill underscores the importance of being recognized as an adult, Roberts furnishes in detail the means leading to an employer’s recognition of the capable servant specifically as a man.[12] “A good set of knives is a valuable thing, and soon spoiled if not properly taken care of by the man who has charge of them. There is no branch of a servant’s business that will gain more credit for him, from ladies of taste, than keeping his knives and forks in primo bono; as they have many spectators” (7). Taking every opportunity to perfect and exhibit one’s managerial skills—to be the man in charge—promotes both an internal and external sense of one’s masculinity.

32In writing about constructions of black masculinity in antebellum America, James and Lois Horton have argued that while aggression was often a valued trait of white masculinity in the early nineteenth century, for black men wishing to assert their manhood the use of violence only served to reinforce the prevailing stereotype (and frequent justification for slavery) of their “inherently” barbaric nature—one of the reasons why violent uprising was often controversial among Abolitionists. This seemed to leave black men with two extreme examples: the emasculated Uncle Tom/Sambo vs. the brute savage (80–84). But by the 1830s, a new, non-violent masculine identity emerges, led, according to Horton and Horton, by William Lloyd Garrison—the same man who would later publish Roberts’s report from the Anti-Colonization meeting in his newspaper, the Liberator. “The route to manhood, he believed, was through strength of character and principled action” (85). As Horton and Horton further point out, Garrison’s masculine ideal, “characterized by intellectual achievement, personal dignity, and moral responsibility,” was particularly appealing to black abolitionists who were concerned with disproving claims of inherent inferiority promoted by Thomas Jefferson, among others (86).

33Long before he is likely to have heard of Garrison, Roberts exemplifies this masculine ideal and encourages his readers—both servants and masters—to do the same. While he cautions servants to control their “tongue and passions” when angry, as noted above, he gives similar advice to employers in “A Word to Heads of Families”: “Impose no commands but what are reasonable, nor reprove but with justice and temper; the best way to ensure which, is never to lecture them, till at least one day after they have offended you” (143). Though certainly not as vulnerable to consequences as their employees, employers too could lose respect and undermine their professional positions by losing their temper. Restraint and self-control for Roberts was not emasculating or subservient but rather proof of one’s inherent dignity and self-management, no matter one’s race or class.

34As many historians have noted, segregation and discrimination against African Americans were commonplace in antebellum Boston, leaving few fields of employment open.[13] Although there were some notable exceptions, most were closed out of the skilled trades and professions. Women, especially the Irish, also faced this challenge. While Roberts could not immediately resolve that issue, by virtue of both its mere publication and its contents, his Directory raises the respectability of one of the fields that was open, changing the image of domestic service from a job many thought of as unskilled, to a meaningful profession with significant responsibilities. As Mary Trueblood will note in her study of domestic service in 1902, a lack of belief in the dignity of labor in general and the importance of their own work in particular is in large part responsible for the dissatisfaction of most servants (2692). In restoring that sense of dignity and value to domestic service, Roberts explicitly extends that dignity to his fellow African-Americans who had few other avenues.

35In answer to other servants who complained about the lack of opportunity for promotion, Roberts shows that there is always the possibility of self-improvement, which could be motivating and satisfying to the ambitious and bestows a sense of control over one’s destiny. There was also the possibility of exchanging one position for another more lucrative, comfortable, or prestigious one, such as Roberts ultimately becoming the head servant in the household of the former governor of Massachusetts. Servants, Katzman has argued, could be seen as “radically excluded” from the American ideals of freedom and personal responsibility (240). In explicitly connecting the servant’s success to his efforts and talents, Roberts undermines this infantilized image. And by proving one’s ability in one field, one could perhaps contribute to the opening of other avenues of advancement.

36Two decades after the publication of Roberts’s Directory, Tunis Campbell will publish Hotel Keepers, Head Waiters, and Housekeeper’s Guide. Both his guidebook and his life show Roberts’s influence as well as represent, in great respect, his aspirations. Like Roberts, Campbell started out as a servant, in his case working in various hotels in New York and Boston. Also like Roberts, he would become an active Abolitionist and, though initially a supporter, vigorously campaign against the American Colonization Society. (In another striking coincidence, both men happen to be buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in Everett, Massachusetts.) After moving to Georgia and working for the Freedmen’s Bureau, Campbell was elected to congress in 1868, only to be expelled from office in the backlash against Reconstruction. While his political career was overtly devoted to equal rights, his guidebook—like Roberts’s—is as notable for its emphasis on the dignity of labor and the importance of improving interracial relationships as it is for his advice on hotel management. And though he does not mention him directly, Campbell must have been strongly inspired by Roberts’s work as he echoes many of his most cherished tenets.[14]

37His guidebook, Campbell states, is intended not only for hotels but also for private families, as “There can be nothing of more importance to a family than the careful attention of faithful servants, in whom confidence can be placed, with the assurance that to the utmost of their ability, both of will and deed, they will work for your benefit” (5–6). In order to achieve that goal, families need to “employ persons that understand their business” (92). And servants must study to become those persons: “In fact, waiters ought to make themselves acquainted with every thing with which they may be practically associated. The way to cause them to qualify themselves, is to encourage them by creating a demand for such a class of persons. Then waiting becomes what it ought to be—a science, which every man who seeks employment in must first study, the same as any other profession” (58). This means, as Roberts discussed, hiring the best help available and compensating them appropriately (8). The interests of the employer and employee must become intertwined, Campbell stresses, and when the employer demonstrates confidence in his employees—treats them as the men Roberts insists upon—he generates a desire within his servants to be worthy of that trust (6–7). Respectful treatment of one’s servants is an indispensable element of engendering shared interests: “A kind word or look is never thrown away upon a servant. This should always be borne in mind by those who have servants under their care or in their employ. In fact, it rests mainly with the employer to make servants either good or bad” (93). Respectful treatment and a recognition of shared interests also, as Roberts indicates, makes good citizens and a strong republic.

38Viewed from the perspective of the twenty-first century, the desiderata of professionalism underlying the writings of these authors remain both topical and most impressive. Their definitions of professionalism, though applied to manual labor, broach the universal and call attention to the inherent dignity of work. In envisioning a contractual relationship between servant and employer, with responsibilities being divided among them, they convey a standard of common enterprise and mutual respect.

39In his writing, Robert Roberts takes matters several steps further by insisting that household servants were practicing what amounted to a craft. What were its constituents? Above all, employer and employee were engaged in the common pursuit of elegance. The employer was obliged to provide the help with proper tools and the means of donning proper attire. There were to be performance standards applied to a work place wherein mutual appreciation and solicitude prevailed. The staff was to act collegially and to be possessed of a certain entrepreneurial spirit conducive to seeking advancement either within the current or a future household. In so prefiguring later calls for fundamentally changing our understanding of this work and these workers, Roberts presents us with a definition of professionalism that remains largely applicable today. Moreover, as he clearly believed, professionalization could be a step toward resolving much more than the “servant problem.” Underlying the pride taken in a job well done was the belief in the efficacy of effort and hard work and the sense of self determination that that engendered. The pinnacle of being recognized as fully human, of being acknowledged as performing vital tasks with distinction and of cultivating a sense of self-possession, would be emancipation.

Notes

[1] Goodman’s last name is spelled “Godman” in her first publication in the Independent (“Ten Weeks in a Kitchen”). I have taken the later spelling as the corrected version. It is clear that she is the same author as there is an editor’s note at the beginning of the second article (“A Nine-Hour Day for Domestic Servants”) reminding readers of her previous contribution.

[2] For a more in-depth study of Alcott’s experiences and views on domestic service, see Maibor “Upstairs, Downstairs, and In-Between: Louisa May Alcott on Domestic Service,” 65–91. In Little Women, though the main character Christie is, like Alcott, white and raised middle-class, Alcott includes an in-depth depiction of another servant, Hepsey, a run-away slave who becomes a mentor and eventually a mother figure to Christie. Alcott extends her insistence on a relaxation of social barriers to race when she has Christie refuse to eat before Hepsey, as the previous white servants had: “I suppose Katy thought her white skin gave her a right to be disrespectful to a woman old enough to be her mother just because she was black. I don’t; and while I’m here, there must be no difference made. If we can work together, we can eat together; and because you have been a slave is all the more reason I should be good to you now” (22). Just as Roberts will argue for the dignity of labor, Hepsey also tells Christie that she does not mind doing the work Christie initially objects to as degrading, because it is free labor (21). It seems likely that Alcott would have at least been familiar with Roberts, if not actually a reader of his Directory. Not only was the Alcott family actively involved in the Abolitionist movement, but they were personally acquainted with William Lloyd Garrison, who published Roberts’s “A Voice from Boston” in the Liberator in 1831.

[3] Pettengill’s argument is anticipated by Margaret Sangster who insists that the business model will not work because of the “elastic” nature of family life, which cannot be regulated like a mill or factory. She also rejects the idea that a more “systematic house mistress” and more clearly defined duties and hours are the solution. Like Alcott, Sangster believes rather that the “possibility of sincere friendship, which softens, blesses and purifies the whole situation” will make household labor more attractive and not merely elevate it, but elevate it “to the region of the ideal” (2605). Unlike Pettengill, however, Sangster never worked as a servant and can therefore only represent the mistresses’ perspective.

[4] Roberts’s second son was named after Benjamin Franklin, and as Hodges has pointed out, his emphasis on rising through ability and effort shows Franklin’s influence on him (xxix).

[5] Roberts instructs servants to get in the habit of rising at least an hour before the family so as to complete “the dirtiest part of the work” without interruption and have the opportunity to clean themselves and change their clothing (3). This allows them to present a professional appearance, but does hide some of their greatest effort. Parties, on the other hand, are a public performance for the servant as well as the host.

[6] See Immanuel Kant’s The Third Critique.

[7] James and Lois Horton have argued that the responsibility of protecting one’s family was a primary aspect of masculine ideals throughout all strata of antebellum American society. Here, Roberts goes a step further showing a black man in the role of protector of a white family (89). [I am indebted to Hodges’s “Editor’s Introduction” for calling my attention to the essay by Horton and Horton.] In the “Receipts” section of his Directory, Roberts shows several other ways he served as protector and caretaker of his employer’s family, including such recipes as: “To Recover a Person From Intoxication” (86–87), “To Know Whether a Bed is Damp or Not, When Travelling” (95), and “To Cure Those That Are Given to Drink” (99). In highlighting these responsibilities, Roberts underscores this as work that matters.

[8] In discussing servants’ meals, Roberts writes that they should ideally sit down together “thankfully” and not “quarrel and dispute with each other, as very often is the case in families” (60). Their relationships with each other should be friendly, certainly, but professional.

[9] Roberts was hired by Christopher Gore after Gore’s visit to his friend, Nathan Appleton. In his apology to Appleton, Gore said he received a letter from Roberts, informing him of his interest and availability—demonstrating Roberts’s initiative in furthering his career. See: Hodges xi.

[10] Roberts knew from painful, personal tragedy that simply being outside of a slave state was no protection. Three of Roberts’s brothers-in-law—born free in New Hampshire, sons of a distinguished Revolutionary War soldier—were kidnapped and sold into slavery. One son, William, managed to escape to England. Another, James, was seen in New Orleans in chains. The third son, Aaron, was never heard from. See: Roberts, “Affidavit” x.

[11] In 1831, Roberts joined a committee to plan a Manual Labor College in New Haven, Connecticut, with the expressed purpose of providing young black men with practical training for the mechanical and agricultural professions. Local white opposition was so strong, however, that the committee ultimately concluded the college would have to be built elsewhere. Graham Hodges theorizes that David Lee Child, who printed Roberts’s affidavit (see note 11), was influenced by Roberts into founding the Noyes Academy in New Hampshire the following year. See: Hodges xxii.

[12] It should be noted that female servants also felt the sting of being treated as girls rather than women. Lucy Maynard Salmon provides a number of examples of female servants bristling at being addressed by their first names, even by strangers, or even worse, by only their surnames, implying both the infantilizing Pettengill complains of as well as social inferiority. See: Salmon 156–57.

[13] Roberts’s son, Benjamin, will later make a name for himself suing the city of Boston over the segregated school system that forced his daughter, Sarah, to walk past five segregated public schools to get to a sub-par private school for black children. Presiding judge Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw decided against Roberts, introducing racial discrimination into Massachusetts law and creating the “separate but equal” philosophy that would ultimately inform the more widely known Plessy v. Ferguson case. See: Hodges xxvi–xxviii.

[14] Roberts’s book was quite popular, going into its third edition by 1837. It is hard to imagine that Campbell would not have been familiar with it.

Works Cited

Alcott, Louisa May. Little Women. Boston: Roberts Brothers. 1868/1869. Print.

—. Work. 1873. New York: Penguin, 1994. Print.

Beecher, Catharine E. and Harriet Beecher Stowe. The American Woman’s Home. 1869. Hartford, CT: Stowe-Day Foundation, 1987. Print.

Campbell, Tunis G. Hotel Keepers, Head Waiters, and Housekeepers’ Guide. Boston: Coolidge, 1848. Print.

Dudden, Faye E. Serving Women: Household Service in Nineteenth-Century America.

Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 1983. Print.

Goodman, Inez. “Ten Weeks in a Kitchen.” Independent 53 (1901): 2459–64. Print.

—. “A Nine-Hour Day for Domestic Servants.” Independent 54 (1902): 397–400. Print.

Harland, Marion. “Why Not?” Independent 51 (1899): 2291–93. Print.

Hodges, Graham Russell. “Editor’s Introduction.” Robert Roberts. The House Servant’s Directory. 1827. Ed. Hodges. Armonk, NY: Sharpe, 1998. xi–xlii. Print.

Horton, James Oliver, and Lois E. Horton. “Violence, Protest, and Identity: Black Manhood in Antebellum America.” Free People of Color: Inside the African American Community. Ed. James Oliver Horton. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Inst. P, 1993. 80–97. Print.

“The House Servant’s Directory.” Rev. of The House Servant’s Directory, by Robert Roberts. Critic 1 (Nov. 1828–May 1829):157. Print.

Kant, Immanuel. Kritik der Urteilskraft. 1790. Critique of Judgement. Trans. Werner S. Pluhar. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1987. Print.

Katzman, David M. Seven Days a Week: Women and Domestic Service in Industrializing America. New York: Oxford UP, 1978. Print.

Maibor, Carolyn. “Upstairs, Downstairs, and In-Between: Louisa May Alcott on Domestic Service.” NEQ 79.1 (Mar. 2006): 65–91. Print.

Pettengill, Lillian. Toilers of the Home: The Record of a College Woman’s Experience as a Domestic Servant. New York: Doubleday, 1903. Print.

Roberts, Robert. “Affidavit of Robert Roberts, of Boston: An Account of the Kidnapping of James Hall, Son of Jude Hall, Exeter, New Hampshire.” David Lee Child. The Despotism of Freedom; A Speech at the First Anniversary of the New England Anti-Slavery Society. Boston: Boston Young Men’s Anti-Slavery Assoc. for the Diffusion of Truth, 1834. 69. Print.

—. The House Servant’s Directory. 1827. Ed. Graham Russell Hodges. Armonk, NY: Sharpe, 1998. Print.

—. “A Voice from Boston.” Liberator 1.11 (Mar. 1831): 42. Print.

Salmon, Lucy Maynard. Domestic Service. New York: MacMillan, 1901. Print.

Sangster, Margaret E. “Within Our Gates.” Independent 51 (1899): 2604–06. Print.

“A Servant Girl’s Letter.” Independent 54 (1902): 36–37. Print.

Trueblood, Mary E. “Housework versus Shop and Factories.” Independent 54 (1902):

2692. Print.

Author

Carolyn R. Maibor is a Professor in the English Department at Framingham State University where she teaches courses in African American Literature, Critical Theory, Early through Nineteenth-Century American Literature and Philosophy, and Gender Studies. She is the author of Labor Pains: Emerson, Hawthorne, and Alcott on Work and the Woman Question (Routledge, 2004) as well as numerous scholarly articles.

Suggested Citation